Fiber Artist

The canvas-sized quilts of Linda Martin '75 aren’t meant to keep you warm.

Her canvas-sized quilts aren’t meant to keep you warm. They’re meant to tell you a story.

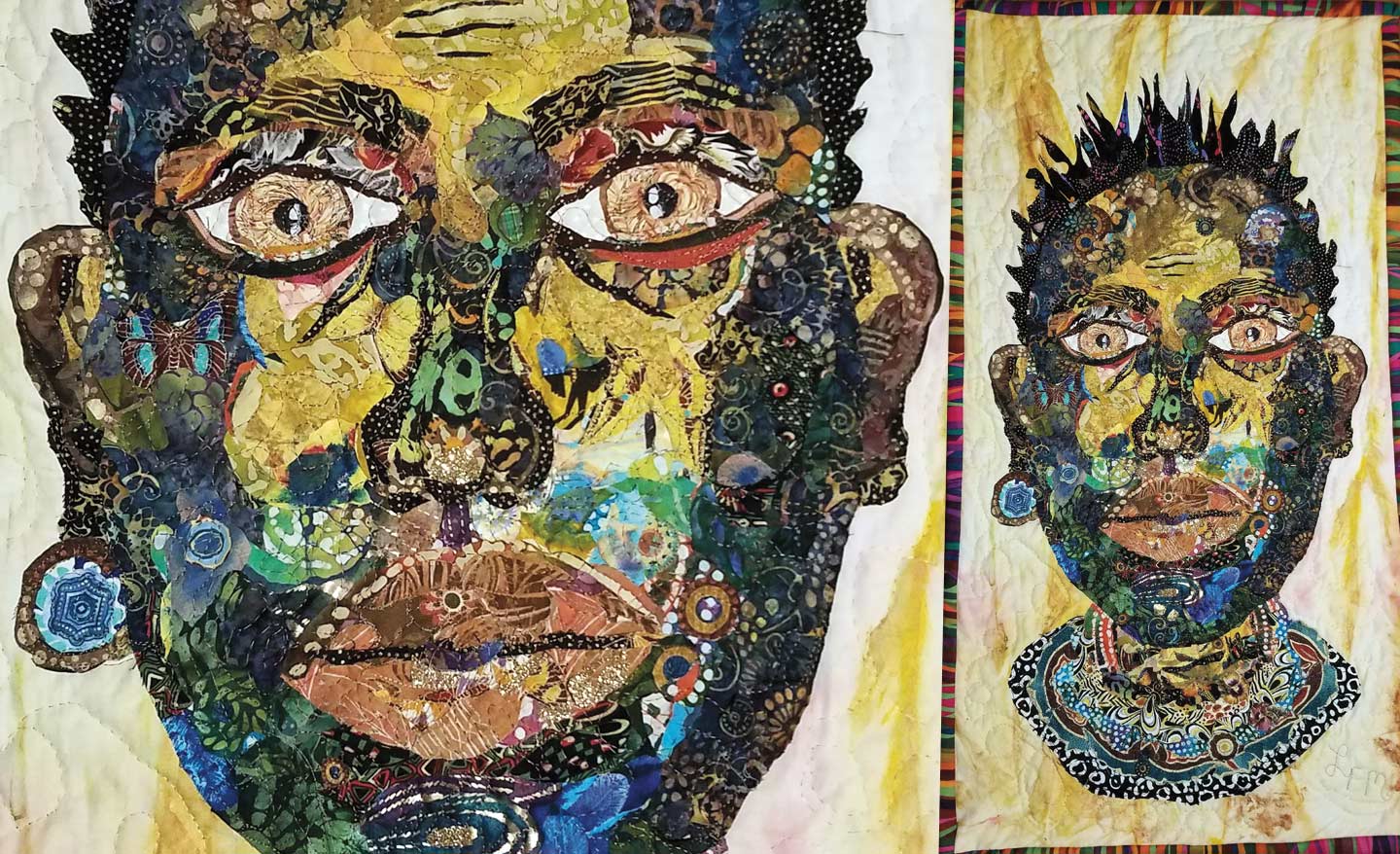

Linda Martin ’75 layers small pieces of synthetic and natural fabrics, each no larger than two inches, to create whimsical portraits of the famous and the unheralded. There’s Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., emerging from swirls of orange and red on one side and flowing blues and greens on the other. Dr. Pearl Primus, the famed dancer and choreographer credited with bringing African dance to American audiences, is depicted with tiny figures dancing throughout her headscarf. A collage of textures and patterns—including animal print and geometric shapes—forms a strikingly lifelike image in “Manchild.”

“I hide things in my quilts,” Martin says, such as four stars in Dr. King’s tie meant to represent his children.

“If you are in a doctor’s waiting room and one of my quilts is on the wall, I want you to be able to sit there for 20 minutes and continue to find something new. I want to engage you.”

These days, you are just as likely to find Martin’s work in a gallery. This spring, much of her collection was on display at the Sidewalk Gallery in Norwalk, Connecticut. A rising star in the world of fiber arts, she is now getting requests to exhibit her work across the country.

Martin worked as an education administrator for the state of Connecticut for 31 years. She liked the job, and it paid the bills, but it wasn’t her passion, and she remembers praying that someday her calling would reveal itself.

That moment came in 2010 when Martin went to the Hartford Stage to see “Gee’s Bend,” a play about women in a small community in Alabama made up mostly of descendants of former slaves who developed a unique style of quilting, creating functional masterpieces that celebrated their cultural histories and family milestones.

“My great-grandmother taught me that quilting was a way of communicating between women,” Martin said. “I realized, ‘I can do quilts.’”

She started out making bed quilts for family and friends, but quickly developed her own style—as she does in just about everything in life.

“I don’t like to be pegged. If you put me in a group of people who look just like me, I’m going to twist my hair or wear green lipstick just so that I’m a little bit different,” she says.

The more people took notice and complimented her work, the more Martin quilted. Still, it took time for her to recognize herself as an artist.

“A few years after I started, my mentor said to me, ‘You are a fiber artist.’ I said, ‘No, I’m not an artist.’ I have great respect for artists. I didn’t think I was one.”

Connecticut College, she says, is an important part of her history as an artist. Martin studied psychology, learned to express herself with writing and nurtured a love of architecture. But it wasn’t always an easy time to be at the College. Martin arrived on campus with one of the first classes admitted after students demanded the College’s administration take steps to diversify the student body and actively recruit underrepresented students.

“We wore big Afros and platform shoes and lived in Blackstone dorm. We had a black student organization and started Unity House,” she remembers. “When I graduated, I wanted to show who I was, that I could combine graduating from Connecticut College with being a woman of African descent. I put red and green stripes down my black gown, and I liked my Afro, so I didn’t wear my mortarboard.”

Martin’s one regret is that she never took a class with Barkley Hendricks, the late professor emeritus of studio art. At the time, she says, she never imagined she’d be where she is today.

“Things have just blossomed,” she says. “I’m now traveling the country with my work in exhibits. I don’t know what this is going to become. But I’m having fun.”