Hope

Susan Guillet ’94 is director of clinical operations oncology at the biotech that developed the first drug to show a “clear-cut effect” in treating COVID-19.

Shortly after returning from Wuhan, China, a man fell ill with a persistent fever and cough, symptoms consistent with COVID-19, the disease caused by the novel coronavirus. On Jan. 20, 2020, the man checked into Providence Regional Medical Center in Everett, Washington.

He was, at the time, thought to be Patient Zero for COVID-19 in the U.S.

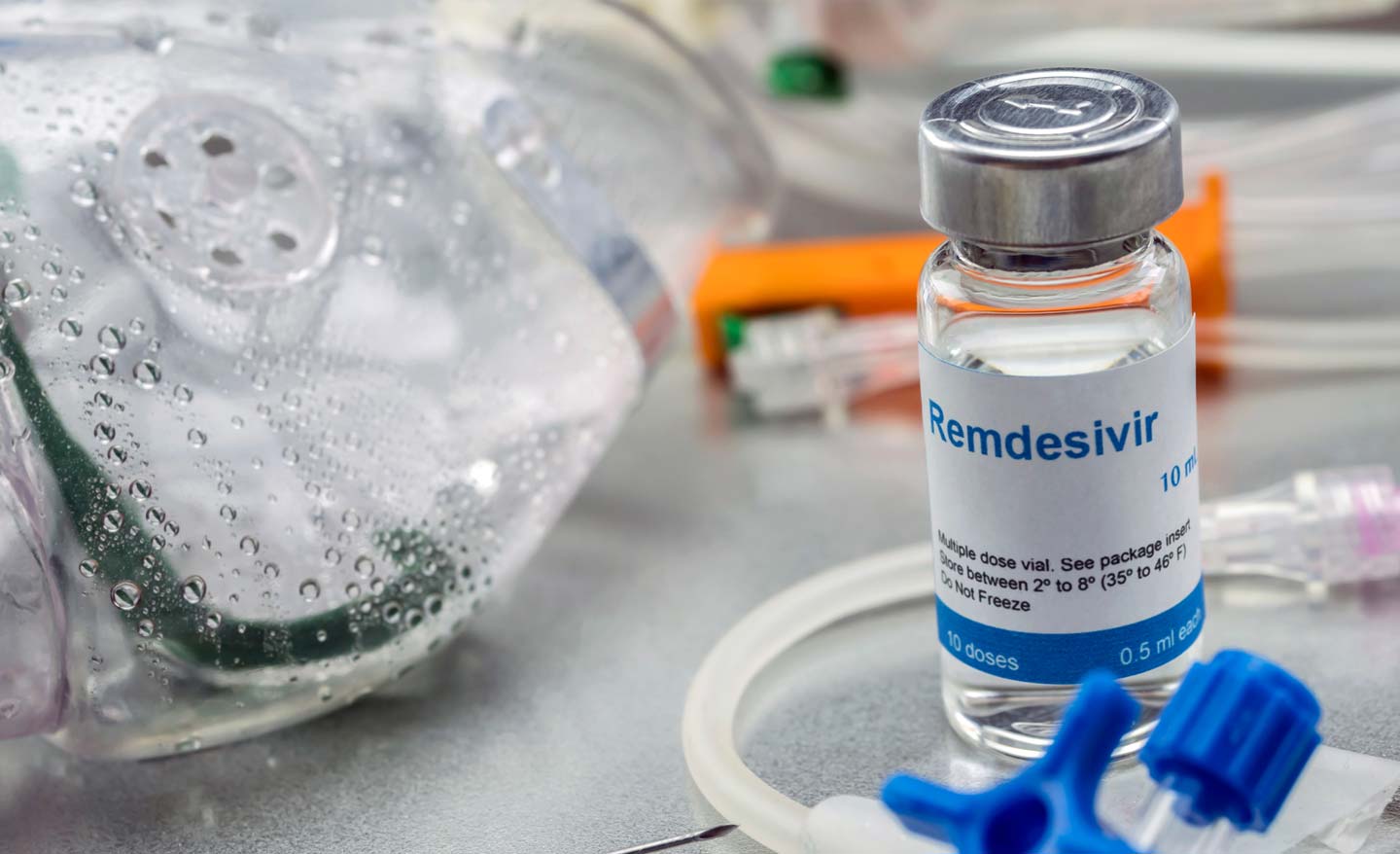

Stable when admitted to the hospital, the patient’s health quickly went sideways. He required oxygen. Chest x-rays revealed pneumonia. Doctors administered intravenously an antiviral drug that had shown efficacy in animal trials for the treatment of Ebola, the virus that ravaged the West African nations of Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone from 2013 to 2016, killing more than 11,000.

Desperate times called for desperate measures.

With the investigational drug remdesivir flowing through his blood, Patient Zero showed improvement overnight. He eventually recovered, and doctors sent him home.

One patient’s positive response doesn’t prove the drug treats a disease, because there are numerous factors—including the important question of whether the patient’s response to the drug was coincidental.

After Patient Zero’s story circulated through the U.S. medical community, though, requests for remdesivir poured in.

It was suddenly “all hands on deck” at Gilead Sciences, the biopharmaceutical company that produces the antiviral, said Susan Guillet ’94, director of clinical operations oncology at Gilead.

“We are pulling in all hands on deck because we want to process as many requests for the drug as possible,” said Guillet, whose team has been engaged in the fight against COVID-19.

Production of remdesivir has kicked into high gear. As of now, Gilead has 1.5 million doses, enough for 140,000 patients. The company is working with partners around the world to boost its manufacturing. Its goal is to produce more than 500,000 treatment courses by October and more than 1 million treatment courses by the end of this year.

It’s clear today, however, that more treatment courses of the drug will be needed.

At the end of April, Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), told reporters that “remdesivir has a clear-cut, significant, positive effect in diminishing the time to recovery” from COVID-19.

The research that led to remdesivir began as early as 2009, through trials underway at the time to fight hepatitis C and respiratory syncytial virus. Gilead produces many drugs, including Harvoni and Epclusa, which have essentially cured hepatitis C, as well as PrEP™, which reduces the risk of sexually acquired HIV-1 infection in adults and adolescents.

During the Ebola outbreak, remdesivir showed efficacy in blocking the Ebola virus in rhesus monkeys. Under “compassionate use” protocols, a small number of Ebola patients received the drug. While the drug proved less effective than others against Ebola, the research established its safety profile. Subsequent trials showed antiviral activity against MERS and SARS, both coronaviruses said to be structurally similar to COVID-19.

Showing promise and obtaining regulatory approval are two different matters. However, as death totals rapidly rise, hospitals overflow with critically ill patients, and supplies of personal protective equipment and ventilators dwindle, doctors are desperate to find anything to treat this virus. After Patient Zero recovered, scientists set up trials across the world: in Wuhan and here in the U.S., both at Gilead and run by the NIAID. Some of these trials were nonrandomized, while others were randomized, meaning that some patients received remdesivir and others received a placebo.

“Data from controlled clinical trials are required to prove both safety and efficacy,” Guillet said, adding that proper dosing also needs to be worked out. “We are conducting randomized trials in patients across different demographics and varying symptoms: those in critical condition (on ventilators); patients in severe condition, who need oxygen support; and patients who are in moderate condition.”

Guillet’s team works in six-hour shifts processing individual requests for compassionate use of remdesivir, then return to their routine responsibilities of managing oncology trials, which still need to proceed within specified timelines.

It’s a pandemic. People at Gilead are working on weekends, seven days a week. “Our chairman and CEO [Daniel O’Day] has been on the phone routinely with the White House and with the FDA and other regulatory agencies around the world,” Guillet said.

That work has paid off.

In a randomized controlled trial overseen by NIAID, patients on remdesivir had a 31 percent faster time to recovery than those on a placebo. The NIAID study was composed of 1,063 patients who were hospitalized with advanced COVID-19 and lung involvement.

“Specifically, the median time to recovery was 11 days for patients treated with remdesivir compared with 15 days for those who received placebo,” the study showed.

Dr. Fauci told reporters, “Although a 31 percent improvement doesn’t seem like a knockout 100 percent, it is a very important proof of concept, because what it has proven is that a drug can block this virus.”

Remdesivir works by blocking the virus’s ability to replicate. The drug is designed to interfere with an enzyme the virus uses to copy its RNA genome, rendering the coronavirus unable to infect other cells.

The global pandemic blew Guillet into the eye of the hurricane. She majored in government and never dreamed she’d end up in the field of science, describing herself as a “typical liberal arts student.” But project-managing oncology trials prepared her to handle the pressure of the pandemic, because patients typically only enroll in clinical trials when very ill and established treatment protocols have failed them.

“I’ve run many clinical trials that don’t work. Sometimes my team gets down if a trial doesn’t hit the primary end point. They take it personally, like they let down the patients. But positive or negative, you are still finding out answers to important scientific questions.

“Is a drug safe or not? Does it work?” Guillet said.

The urgency of this moment is different, as the global death rate from COVID-19 continues to rise.

Guillet has read some of the “heartbreaking” correspondence her company has received, pleading for remdesivir. She has, like all of us, seen the brutal images of field hospitals and refrigeration trucks parked outside hospitals to store the overflow of the dead. She’s proud that her company is in the thick of the fight to defeat this virus.

“You hear a lot of negative stuff about pharmaceutical companies, but I take it with a grain of salt. The primary reason people work at Gilead is to help patients. To see that a drug is benefiting patients makes you want to go to work every day.”

Gilead CEO O’Day has pledged to donate 1.5 million vials of remdesivir—“the entirety of our supply through the early summer”—for use in clinical trials, compassionate use cases and beyond.

Meanwhile, clinical trials for remdesivir continue. Gilead is investigating ways to make the drug more convenient for patients, including forms that are injectable under the skin or inhaled. This development is in its infancy. More trials are needed to test patients with less severe cases of COVID-19. And remdesivir is also being tested in conjunction with other drug combinations, such as anti inflammatories.

While the drug did decrease, as Dr. Fauci noted, recovery time by 31 percent, the drug did not significantly reduce fatality rates.

It’s no silver bullet.

However, the Food and Drug Administration, under its emergency use provision, recently authorized the use of remdesivir to treat seriously ill COVID-19 patients. The F.D.A. approval is only temporary.

The medical community, though, is cautiously optimistic.

By Edward Weinman