The Future of Work

The pandemic has altered the way Americans work. Are remote work and flex schedules temporary, or will they become the norm in trying to harness human capital?

If anything is newly calibrated in mid-pandemic America, it’s work.

For how much longer will “the office” and “commuting” be a meaningful part of the vernacular? How much are the bosses even in charge anymore?

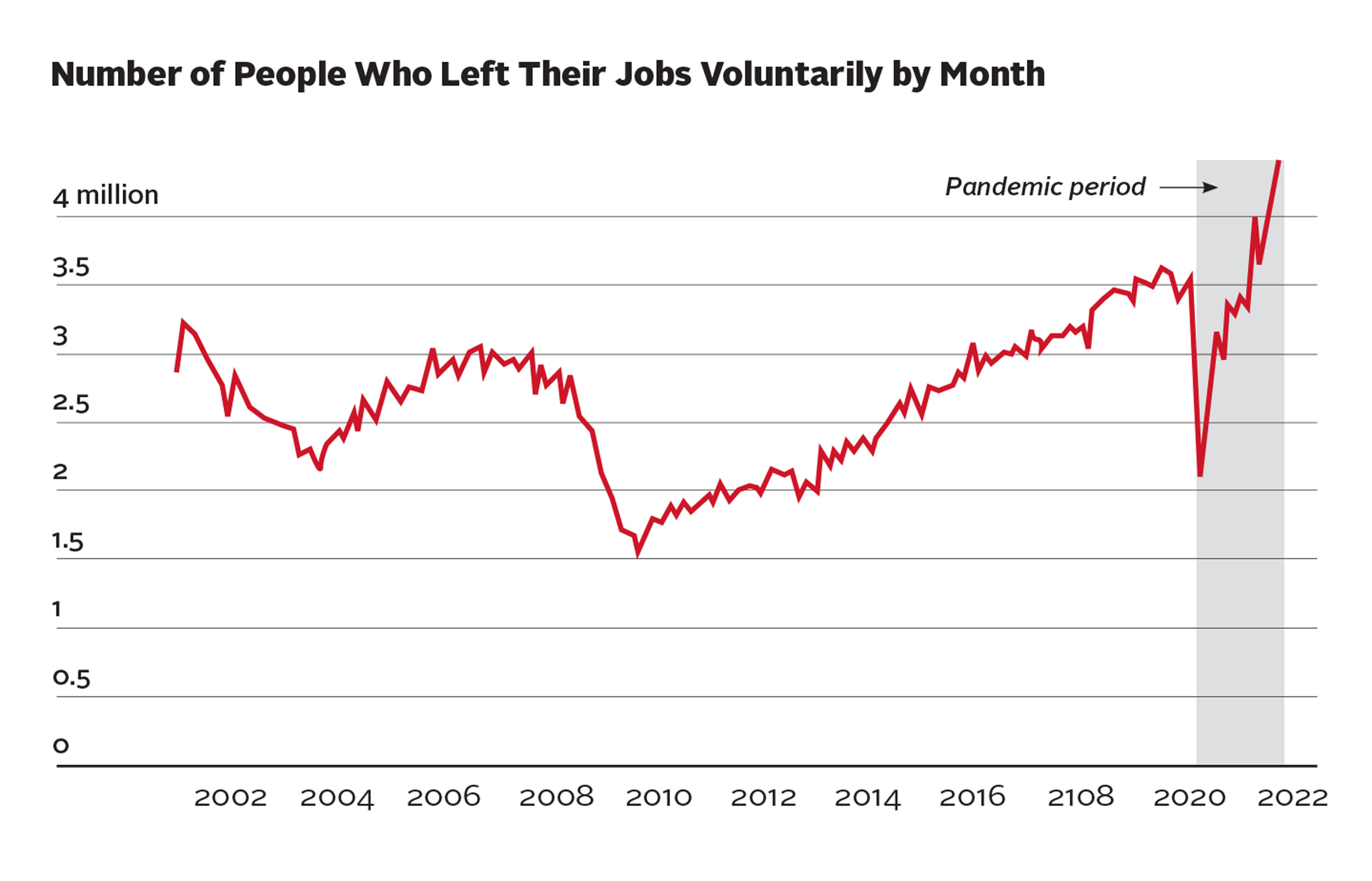

For many months, as COVID-19 gave way to delta and then omicron, the signs have been unmistakable: millions quitting their jobs at a record pace; workers not only holding out for flexibility but demanding that they be made to feel valued; executives, managing the precarious balance, worrying about the loss of corporate culture and, of course, productivity.

So, what is the future of work?

What’s clear is that more of it, pandemic or not, will be done at home.

“I think this is something that has been in slow motion for a long time. What the pandemic did was accelerate the experiment,” said Jay Lauf ’86, co-founder and president of Charter, a New York City media and services company focused on the future of work. “In a lot of ways, the [work-from-home] experiment’s proven that it can be done, and done more readily and effectively.

“My hope is that we won’t necessarily snap back to the way things were before the pandemic, and that there’s a real opportunity to create more long-term systemic change that creates more high-functioning and equitable workplaces,” added Lauf, the former publisher of The Atlantic and WIRED.

The acceleration of remote work caused by COVID-19, said Erin Robertson ’14, human capital manager at Deloitte Consulting in Arlington, Va., “forced leaders to explore and think critically about where work is performed, how it’s done and who exactly does it. I think, specifically from a workforce perspective, the shift toward a hybrid environment proved that people can work efficiently; they can work effectively without being in person.

“I think it also demonstrated how a more flexible work environment can actually attract and retain more diverse and geographically dispersed talent, and it illuminated different cost-saving opportunities.”

THE PANDEMIC JOLT

Among the factors driving the change is a shift in the balance of power away from employers and toward employees. It’s historically significant.

The federal right to unionize (1935), a federal minimum wage (1938) and a 40-hour workweek (1938) came about only after decades of struggle at the ballot box and through strikes, said Mark Stelzner, an assistant professor of economics at Conn, whose research focuses on income inequality in the United States. Since the 1980s, some of the worker gains have eroded and union membership has plummeted. The emergence of the coronavirus brought a resurgence in worker power.

“In terms of COVID, there was this jolt to the employer-employee relationship, and this jolt forced many employees in a number of ways to reevaluate their relationship with their employers,” Stelzner said.

Therapists who began counseling patients remotely realized that maybe they didn’t need to be part of a clinic. Front-line workers who were forced to show up on the job and risk their health questioned how much their interests were being considered. Layoffs led some people to downsize their lives; in consuming less, they didn’t need to generate as much income.

Some front-line workers decided the health risks weren’t worth it. They opted for other jobs or perhaps went back to live with their parents while awaiting safer opportunities, Stelzner said. Some who quit jobs did so to protect themselves from COVID-19, or to protect their children by keeping them out of school or child care facilities. Others made a permanent or at least long-term decision. Couples, for example, chose one full-time income instead of two, or one full-time and one part-time income.